A Short Guide to Buddhist Deity Sculptures in Japan

2022/02/17

In your travels throughout the islands of Japan, you will no doubt encounter a large variety of Buddhist statues, whether it be simple weather-worn stone image found on the side of the road, or perhaps magnificent depictions of Buddhas housed in famous temples. The many different deities, symbolism present in the depictions of deities, and so on and so forth, can be overwhelming for anybody who wishes to understand the incredible amount of diverse Buddhist artwork present in Japan.

This article will be my attempt to give a very basic framework for how to understand the most common types of Buddhist sculptures (focusing on deity types) in Japan so that readers can hopefully come away with a basic understanding of the deep meaning behind the artistry inherited from centuries past.

Tenbu

The tenbu (or “devas”) are imposing looking figures who are often first encountered to either side of Buddhist temple entrances. It can be said that they serve as the celestial guardiana of Buddhism. They are usually depicted standing, looking battle ready, and clad in armor with menacing looks on their faces. Sometimes tenbu may be standing with one foot pressing down atop a demon, representing the power of deity to defeat the forces of evil.

There are many named tenbu deities in Japan, but perhaps the most famous is the deity, Benzaiten, a figure who is also worshiped as a kami in Shintoism, which aptly demonstrates the syncretization of the 2 religious traditions over time in Japan. Benzaiten, is commonly associated with wealth, fortune, and also the arts. The Benzaiten-sha Shrine in Nara’s mountain village of Tenkawa contains a special stage whereupon performances are sometimes held to honor the deity.

Red tenbu stand guard at a gate entrance to Sakuramoto-bo Temple in Yoshinoyama.

Bosatsu

“Bosatsu” is the Japanese term for a “Boddhisattva” and was used to in reference to Shakyamuni Buddha (who many simply know as “the Buddha”) before he was fully enlightened. These are beings who are commonly associated with great compassion. They are often depicted much like Shakyamuni during his time as prince, sporting a lot of ornamentation (crowns, jewels, nice clothing, etc.) on their forms. They also may have many hands or faces so that they can engage with all people who are in need of their help.

Bosatsu are probably the most prevelant of Buddhist statue types that you will run into throughout Japan, as they are very popular among the populace for the help they are believed to be able to provide. Jizo or Jizo-sama (“sama” being an honorific term similar to “-san” but of a higher tier) are a type of Bosatsu that are commonly found along the side of roads, cemeteries, and inside temples. Another very prevalent Bosatsu is the deity Kannon, who is sometimes called “the Goddess of Mercy,” but has been depicted as both a male and female. Thousand armed Kannon statues (“Senju-Kannon Bosatsu”) are especially famous, with a few of them found in Nara’s many temples such as Todai-ji, and Toshodai-ji.

Jizo statues at Hase-dera Temple in Nara’s Sakurai City.

Old Jizo statues are partially covered under a fresh layer of snow in Yoshinoyama.

Myo-o

Myo-o are deities of great wisdom who are depicted as intimidating beings, often wreathed in flame and holding a weapon. They are figures who seek to help people who may need more of a kick in the rear to “wake up”, so to speak. The beings are often associated with stricter teachings, such as the deity Fudo-myo-o, whose power is often called upon by the mountain-worshipping Shugendo practitioners known as Yamabushi.

The Yamabushi seek to obtain holy power through special aesthetic training commonly called “shugyo“, often performed in Japan’s rugged mountains in accordance with centuries of tradition. Shugyo will often require some amount of discomfort or great risk of bodily harm to complete, such as waterfall training or navigating dangerous crags without a rope. Therefore, it is not uncommon to see depictions of Fudo-myo in the mountains of Nara along routes that are associated with Shugendo (such the Omine Okugake-michi).

Along the Omine Okugake-michi path in the Yoshino region of Nara.

Fudo Myo-o, is one of the most easily recognizable deities because he almost always is depicted carrying a sword that is used to cut through lies and deception. He also usually has a scowling face (sometimes with fangs that protrude from the mouth), and set of intense eyes.

A very rare stone depiction of Fudo Myo-o found along a trail leading up to the peak of Mt. Ryuo in Tenri City, Nara.

Statue of Fudo Myo-o in Ofusa-Kannon Temple in Sakura City, Nara

Nyorai

Nyorai can be thought of as the highest rank of the pantheon of Buddhist deities; they are the Buddhas or the beings that have reached full enlightenment, such as Shakka Nyorai (the original Buddha) and Amida Nyorai. Statue depictions of the nyorai are highly varied, and they also make up some of, if not the most famous Buddhist statues in the country. Examples of famous nyorai include the Great Buddha of Todai-ji Temple in Nara City (Dainichi Nyorai) and the Great Buddha of Kamakura (Amida Nyorai).

In general, Nyorai are beings that are depicted with serene faces and wearing simple garments which reflect their status as free from attachment. They also usually are given a head with short, curly hair and a rounded bump in the middle that is actually supposed to be a growth out of the top of the skull (not hair) that is one of the characteristic signs of a Buddhahood. As an aside, some people say that the curly hair on a Buddha’s head is not supposed to be hair at all, but instead represents the 108 snails who shielded Shakka Nyorai’s head from the sun’s rays during his long period of meditation under the Bodhi tree.

For an image of the Great Buddha of Todai Temple. see the official website or just try searching for countless other examples using the term “nyorai.”

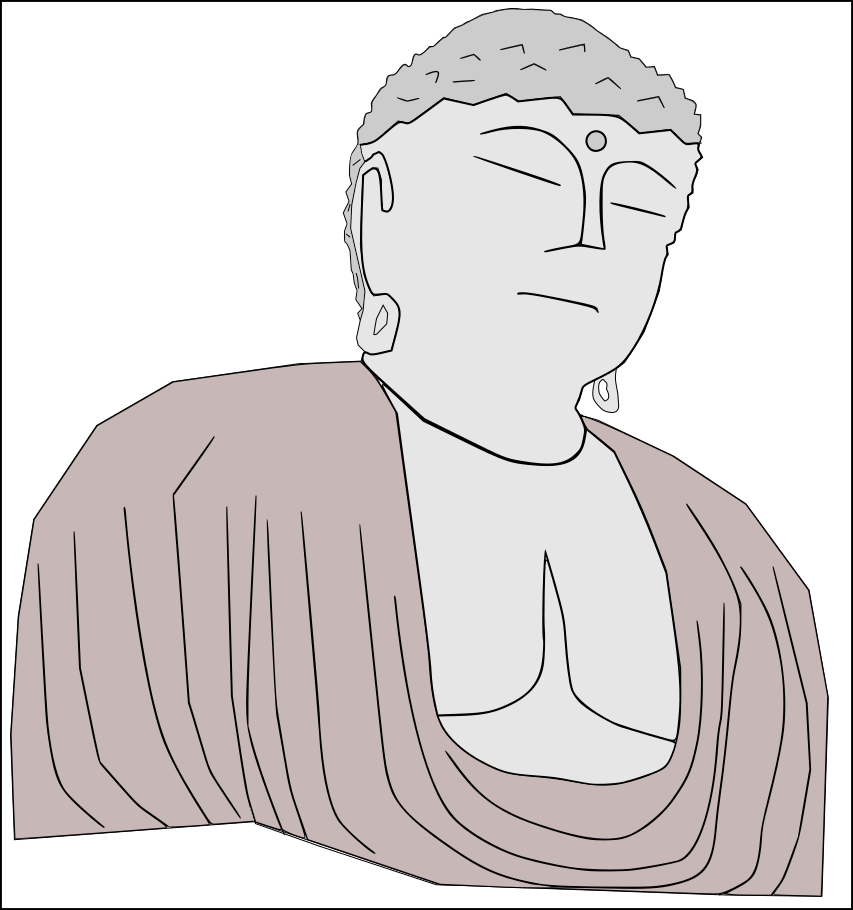

Rough example image of the design of Kamakura’s great Amida Nyorai metal sculpture.

Besides the 4 basic descriptions above, there are many other elements that come into play surrounding how the design of Buddhist deities differ or overlap in Japan and the rest of the world, for that matter. Design points like what is displayed immediately behind a Buddhist figure can also tell you something about who they are or what they are associated with. Furthermore, the distance the Buddha is from the the viewer (or whether or not they are even on display at all) can tell you something as well.

In Nara’s Asuka-dera Temple, which is credited with being the oldest Buddhist temple in the country, the Great Buddha statue is seated right next to where visitors stand, accessible and within arms length of anybody who wishes to visit. As time went on, Buddhism became more esoteric in Japan and therefore the central Buddhist statue of many temples was moved farther back, away from visitors, sometimes even hidden from view.

As you can see, there is an incredible amount to study in regard to the various aspects of design, positioning, material, and so on in regards to Buddhist sculptures in Japan, especially considering the around 1,400 years of history it encompasses. This article only really gives just a (hopefully helpful) taste of what is out there for you to discover.

01

FIND YOUR FAVORITE

TRIP ON OUR WEBSITE.

SEND US AN INQUIRY.

02

PERSONALIZE THE TRIP

TO YOUR INTERESTS

WITH OUR CONSULTANT.

03

20% DEPOSIT TO CONFIRM.

BALANCE PRIOR TO ARRIVAL.

PAYMENT BY CC OR TT.

04

WE WILL

MEET YOU

AT THE AIRPORT.

05

DISCOVER THE

TREASURES!