Natural Treasures: Living with, Photographing, and Summoning (by French Horn) the Sacred Deer of Nara

2023/12/06

The people living in Nara share the city with over a thousand deer who roam freely in its 1200-acre park, in the forests, and even along the shopping and residential streets. They keep the park’s grassy lawns trimmed and, unintentional topiarists, even tidy the trees of their hanging leaves into what are known for their straightness as the “deer-lines”. They are designated National Natural Treasures. We humans may be less accustomed to these normally wild animals than they are to us, so seemingly domesticated have the deer in Nara become, but during the pandemic and in the absence of the crowds of visitors to the park who revel in feeding them the senbei crackers that have become the customary offerings, they quickly reverted to their foraging ways, venturing further outside the park and losing the inclination to “bow” – a gesture that had been learned as a means of soliciting food. As tourists have returned, so too have the behaviours that demonstrate the ways in which the deer became used to sharing space with humans, and this change makes me think of the significance that life with deer has for those who live in, and those who visit, Nara, and the way that they seem to be indelible as part of the image of Nara that all of us hold. The co-existence between Naraites/visitors and the deer has become a defining aspect, and concern, of the city. And they are the postcard-pretty animal image of it, as much a motif as cows are to Dehli, cats to Athens, and pigeons to Vatican City.

In the 19th century the punishment for the killing of a deer in Nara was beheading. It is still illegal: in 2021 a man was jailed for the crime. For centuries, even the natural corpse of a deer found on one’s land subjected one to monetary penalty, leading to the residential practice of rising early expressly in order to survey property and remove any unfortunate evidence of – here– not criminal activity, but impurity. Therein lies the reason for the significance of the deer and the palpable hold they have on the Nara imaginaire, and on the ambience of the city. They are sacred beings, and so their death is greatly dangerous and meaningful for those in its presence, and whether or not this sacred status is truly believed today they are still referred to as “god-deer” (shinroku), and the respect with which they are treated as they wander about at will is quite clear. The sacredness of the deer which ensures their protection has also contributed to their preservation as a species. Shika/Sika deer with their signature spotted coats are native to East Asia but remain in most abundance in Japan.

The god who is now enshrined at Kasuga Taisha Grand Shrine within Nara Park arrived in the region riding a white deer in order to protect the new capital: so goes the story of the ancestor of today’s deer, intrinsic to the origins of the imperial city. In acknowledgment of their roles as messengers of the gods and as symbols, they were incorporated into elaborate ritual art used by Buddhists, the newly prominent masters of the religious technology needed to operate the realm, who shared a sphere of influence with the older Shinto priests. Where the ancestor deer carried a Shinto god on its back, its saddle soon bore Buddhist objects and a largely relic-based form of Buddhist art focused on deer emerged uniquely in Nara. Nara National Museum, also within the park, houses a wealth of such deer-related art. For example, the deer was portrayed as carrying a Buddhist relic encased in a crystal and surrounded by bronze flames – all potent symbols for the Buddhists, as the relic constituted the Buddha himself in microcosm – and the deer here is like a variation of the famous (live) elephants that bear Buddha relics in Sri Lanka. As such, deer have long been absorbed into the religious lives of Nara’s priesthood and devotees and their free-roaming presence and popularity today is a present-day manifestation of this.

Deer-related art influenced by Buddhism: Deer Mandala of the Kasuga Shrine (Kasuga Shika Mandara), late 14th century Japan, Nanbokucho period (1336–92). The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Mary Griggs Burke Collection, Gift of the Mary and Jackson Burke Foundation, 2015

Three events in the lives of the deer of Nara are of especial interest to visitors: the wobbly-legged debut of the fawns in June, the “calling of the deer” (shikayose) in winter and summer, and the antler-cutting ceremony in October. The calling of the deer began in the 19th century, originally as a way to provide food during the colder months when natural foraging is more difficult. On a chilly morning, a French horn player draws hundreds of deer, who often emerge at a gallop out of the forests and from all over the park, with a rendition of Beethoven’s Symphony No.6 ‘Pastoral’ (find the days and times for winter-viewing below). In the autumn, the antlers are sawn off the stags, a physically painless ceremonial operation that can also be viewed by the public.

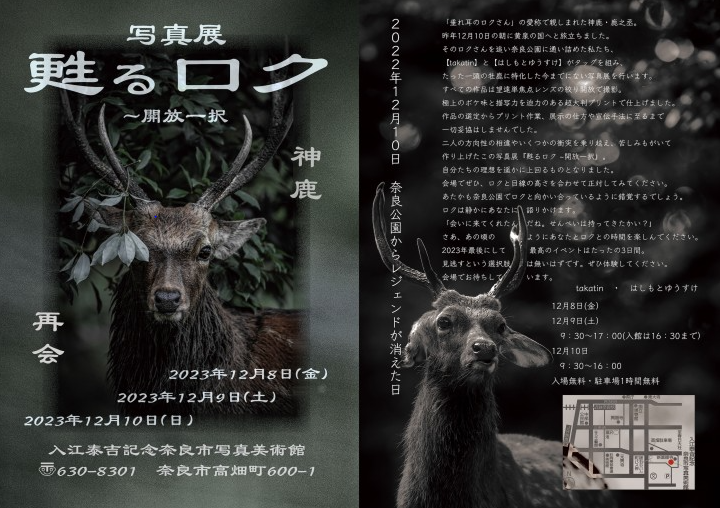

Even a short commute across the park elicits the instinct to snap photos of our cervine neighbours in all their activities and unintentionally charming poses, while a photo with a deer is likely part of every tourist’s itinerary. The animals bring an especial delight to children who have to chance to be in rare proximity to wild things (though deer fans are well-advised to avoid the very special indignity of sometimes quite painful headbutt from behind by deer excited at the prospect of being fed). Other amateur and professional photographers are aplenty, and with them come supermodel deer, and pastures wilder than the centre of the park. The legend “Roku”, a charismatic stag with unusually floppy ears, has been snapped throughout his life by nature portraitists, Taka Miyaura (“Takatin”) and Yusuke Hashimoto.

Their images of deer capture the wildness and majesty of the creatures, as well as their elegance, sweetness, and playfulness – and sometimes odd entanglements with human life, as in Hashimoto’s shot of a stag with a plastic bag snagged on one antler, suffused with sunlight and hanging like an ethereal shed membrane.

What is intimately relatable and what is bestial and otherworldly – both can be sensed through their photos. Takutin also photographs “Pon-chan”, a younger companion of Roku, and Hashimoto a pair of sisters, “Ichiko” and “Niko”. Roku died last year on December 10th, and a memorial exhibition of photos by Takutin and Hashimoto will be on show from December 8th-10th at the excellent Irie Taikichi Memorial Museum of Photography (details below).

Musuem leaflet for “Yomigaeru Roku”, Takatin and Hashimoto Yusuke’s photography exhibition at the Irie Taikichi Memorial Museum of Photography, Nara City.

How to maintain the balance between wildness and domesticity is just as delicate an endeavour as that of keeping nature and culture in harmony as a whole in Nara City. Nothing brings this quite so much to mind as noticing a deer wander nonchalantly past one’s office window of an afternoon, or glimpsing from a table inside one of Naramachi’s French restaurants a pair strutting along a darkened back street, heading who-knows-where into the night. It’s a rather magical intervention of nature into culture. It’s peculiar, discombobulating, and mysterious. It’s surreal and dreamlike. And its one of the many reasons I love to be in Nara. Do we live with the deer, or do they live with us?

Please feel free to contact us here at Kansai Treasure Travel anytime for further details, travel advice, or a custom tour, and see our Walking Tour in Mount Kasuga Primeval Forest and 1 Day Nara and Uji Private Tailor-made Tour

The Calling of the Deer (Shikayose), Winter:

Tobihino lawn in Kasuga-taisha Shrine grounds (Nara Park). A ten-minute walk from Kintetsu Nara Station leads to the edge of Nara Park . From here a walk of about 15 minutes brings one to Kasuga-taisha Shrine.

2023: December 1st – 14th 10am (Note that the dates are subject to weather – and viewing may be affected by the Nara Marathon (Dec 10th).

2024: January 6th – February 25th, every Saturday and Saturday (excluding January 27th & 28th), as well as public holidays Jan 8th (Monday), and February 12th (Monday) and 23rd (Friday).

Entrance: free

Yomigaeru Roku photography exhibition

Irie Taikichi Memorial Museum of Photography Nara City 600-1 Takabatake-cho, Nara 630-8301

December 8th (Friday) – 10th (Sunday), 9:30-5pm (last entry on the 10th is 4pm)

Entrance: free

With thanks to Takatin and Yusuke Hashimoto for the photos used in this feature, including the banner photo, by Takatin.

01

FIND YOUR FAVORITE

TRIP ON OUR WEBSITE.

SEND US AN INQUIRY.

02

PERSONALIZE THE TRIP

TO YOUR INTERESTS

WITH OUR CONSULTANT.

03

20% DEPOSIT TO CONFIRM.

BALANCE PRIOR TO ARRIVAL.

PAYMENT BY CC OR TT.

04

WE WILL

MEET YOU

AT THE AIRPORT.

05

DISCOVER THE

TREASURES!