Genji and the Heian Court at Kasugataisha Museum, Nara

2024/06/21

“The Era of The Tale of Genji: Glories of the Heian Dynasty” is currently running until August at Kasugataisha Museum. The Tale of Genji is a saga and historical courtly romance novel set and written in the Heian period (794-1185) by court lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu. But it is also an exploration of political intrigue and of the complexities of succession. It reflects much of the real-life complication in the Heian period when it came to imperial succession and court appointment from the encroaching, eventually overwhelming, power of the Fujiwara clan who intermarried via the emperor’s harem; the community of the consorts; the fate of an illegitimate heir; the intricate processes of courtship; and the intertwining of aesthetic codes and politics. Murasaki was of the Northern Fujiwara clan, she married a Fujiwara, and she was at court herself. And she wrote, arguably, one of the most gorgeous, epic, and psychologically incisive novels in existence.

*Note that the images shown are not those on display at Kasugataisha (but they are representative of Genji culture, or from the period). See Kasugataisha Museum website for images of some of the exhibits.

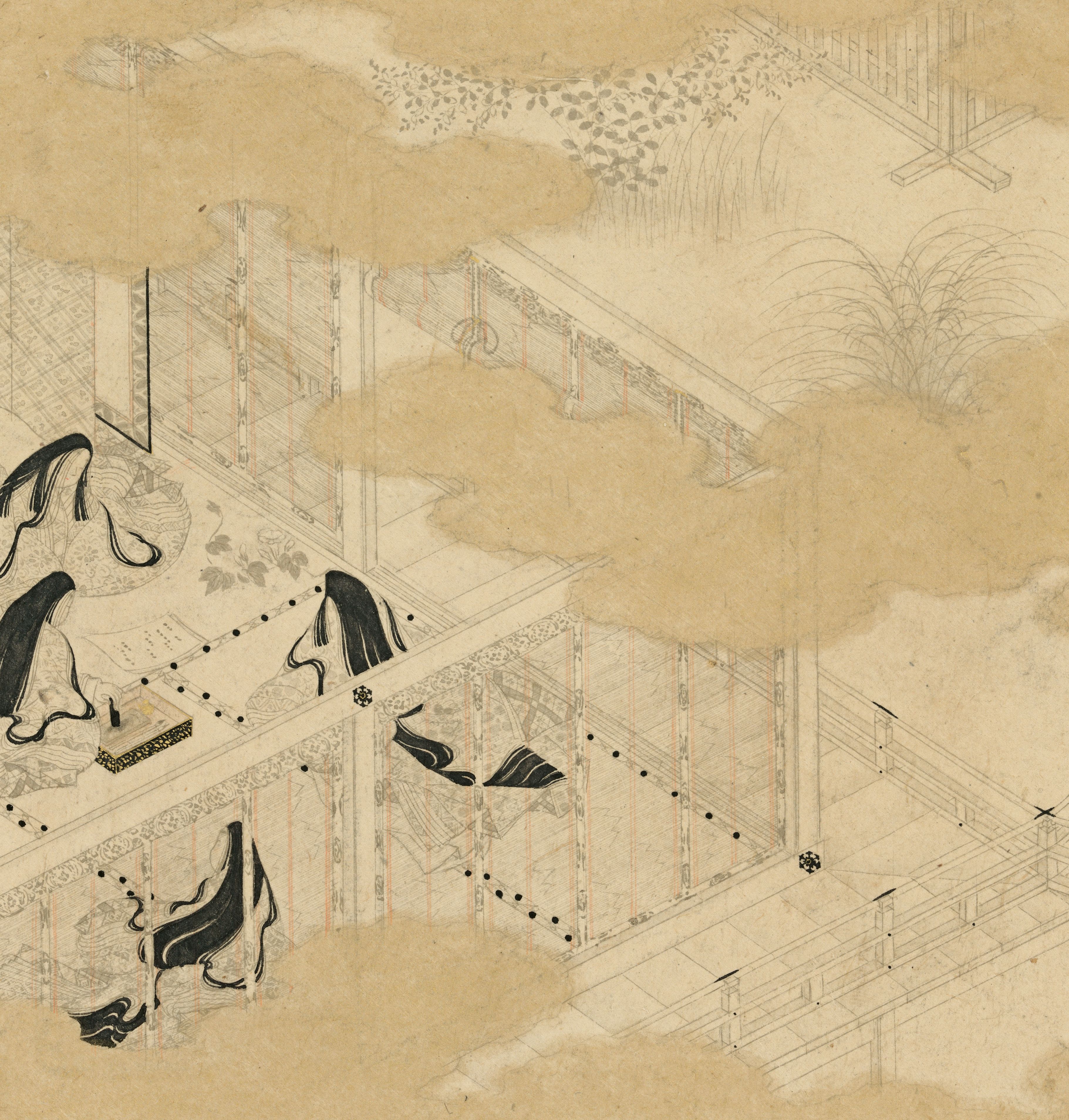

“Albums of scenes from The Tale of Genji” by Tosa Mitsunori. Early 17th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The exhibition focuses on the aesthetics of the era portrayed in the tale, especially (by virtue of the museum site) in their relation to the systems of worship around Shinto gods and grand shrines. Genji is set in Kyoto, and while Nara is at some distance from Kyoto, Kasugataisha was an important Shinto site of worship for the imperial court – the setting of Genji – in large part because it was the tutelary shrine of the Fujiwara clan who married into the imperial family and thereby rose to power as Regents. And Kasugataisha is something of an imperial repository because the Fujiwaras as well as the emperors to whom they were connected would make lavish offerings to its gods whom they believed protected them. So, it was of especial importance from the period in which Genji is set (10th century) until the start of the Kamakura warrior government (12th century) when power shifted from the Fujiwara. The Fujiwara loom large in Genji, and in the exhibition too.

The collection of items on display includes swords, bows and arrows, ornamental works, dance costumes, a folding screen, and picture scrolls as well as a few stunning recent reproductions of such items. One reproduction, which is displayed beside its deteriorated 1131 original, is a flat quiver made of silver-plated rosewood. The slatted board into which arrow tips are lodged, called a yakubari-ita, is inscribed with the information that the quiver had been carried by statesman Fujiwara Yorinaga in a procession to the Sanjo Palace of the Retired Emperor Toba. Five years later, Yorinaga offered it to the Wakamiya god, enshrined at Kasugataisha. Just how gorgeous the entourage must have been is suggested by this one piece of apparel which, probably because of the preservation required by its later sacred status, is one of the only elements to have survived. Also on display are the originals and reproductions of elaborate and elegant swords, a bow, and a set of whistling arrows (kabura-ya) which have tips split like snakes’ tongues, lacquered bamboo bodies, crystals, golden eagle feathers, and “boar’s eye” cut-out motifs (these are heart-shapes found often in decorative arts in Japan that were thought to have the function of dispelling evil).

“Imperial Visit to the Great Horse Race at the Kaya-no-in Mansion” from the Tale of Flowering Fortunes. 13th–14th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Statesman and Regent Fujiwara Michinaga is also present. Murasaki was a court contemporary of this powerful man who brought Fujiwara regency power to its height, and some (such as scholar Kuramoto Kazuhiro) have argued that her novel even played a part in his political machinations. Some large bronze mirrors on display are thought to be related to Michinaga: the calligraphy inscribed on them resembles his, and the date on them corresponds to the year his son made a pilgrimage to Kasugataisha (to which they were offered). A 13th century copy of a 1021 decree by Michinaga’s son-in-law Emperor Go-Ichijo that was to be read aloud in front of the Kasuga gods also indicates the ties between the period of Murasaki’s novelistic creation, imperial rule, and this shrine. According to records, Michinaga was in attendance at this reading, along with Empress Shoshi, mother of the Emperor and the woman upon whom Murasaki waited – and to whom she read her unfolding story, which she presented in installments to the court.

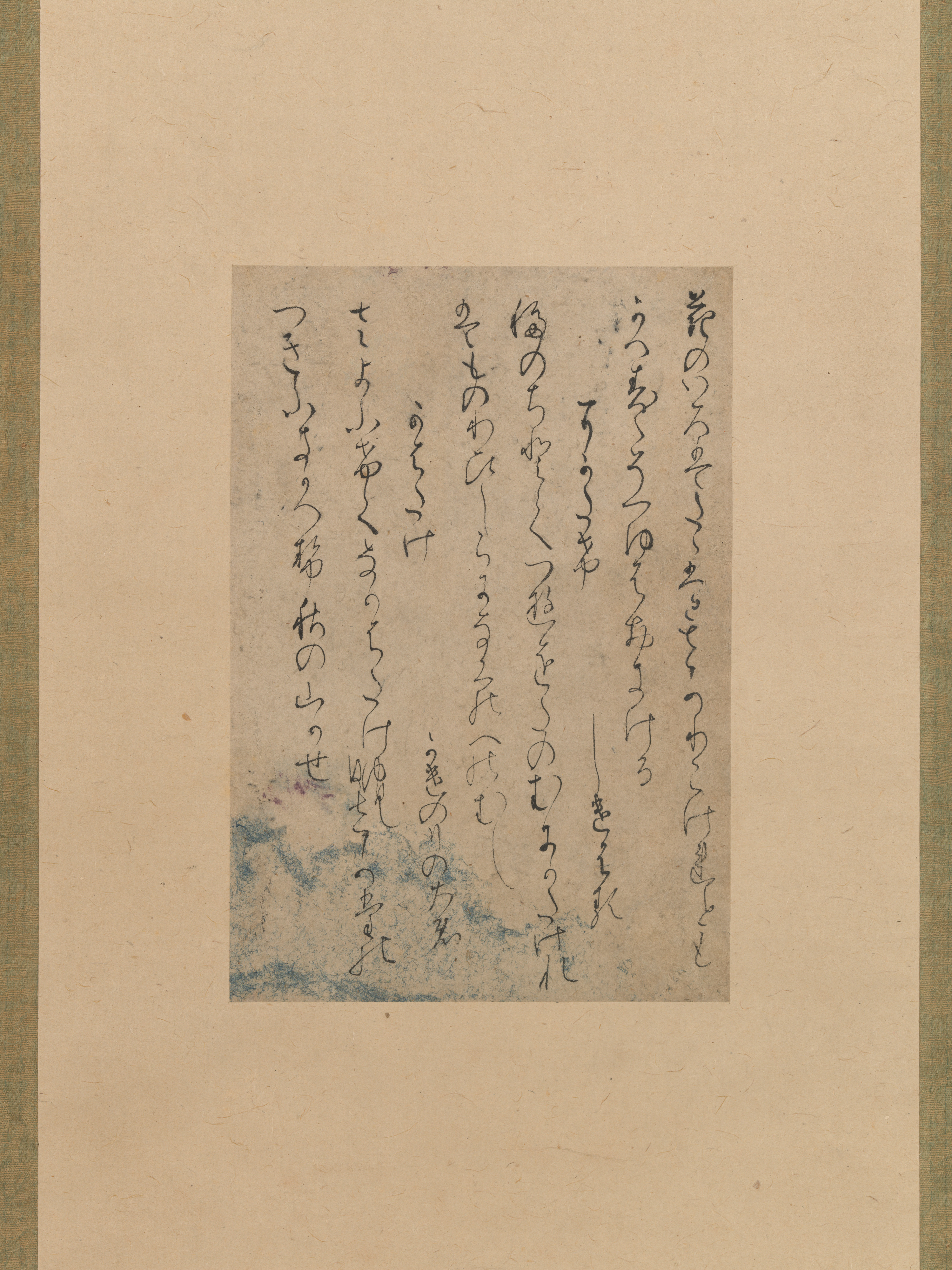

Three Poems from the Collection of Poems Ancient and Modern (Kokin wakashū), one of the Araki Fragments (Araki-gire), attributed to Fujiwara no Yukinari (Kōzei). 11th century. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Other objects are more loosely connected to Murasaki: a set of pieces for the shell game, a popular upper-class past-time in which (in this case) scenes painted on the shells from Genji were matched, and handwritten copies of the novel by a 17th century Kasuga shrine officiant, Nakatomi Sukenori. The Heian aristocracy loved the Azuma Asobi suite of dances, which are described in Genji, and a modern version of the costume traditionally used at Kasugataisha shows some typical decorative motifs – bamboo, pheasants, bursts of paulownia, sandbanks – in plenty of gold and silver. Fujiwara Yorinaga’s diary, entitled Taiki, refers to what is likely the small bronze “Korean dog” (komainu) on display and reveals it was owned by an emperor. This were placed at the entrances to shrines, sometimes with “Chinese lions” as protectors.

Dish with Design of Court Lady by the Gate of a Shinto Shrine. 1650–60s. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

Give or take a few centuries, the show depicts the culture of Genji. In fact, speaking of broad spans of time, the imperial court was famously unprogressive: it was fastidious about precedent and immersed in courtly protocol and pleasure, something that is itself well portrayed in the novel. Fujiwara Yorinaga – he of the exquisite quiver offering to Kasugataisha that is on display beside its perfect reconstruction – (ironically) considered such adherence to outdated practices detrimental to the operations of the court, but regardless, because of the court’s somewhat bubble-like existence what we see in the exhibition can be broadly seen as representative of the life of the high echelons of society in the time of Genji. This beautiful show displays well the relationship between the grand shrine of Kasugataisha and the rulers and political players of the court as reflected in The Tale of Genji.

Kasugataisha Museum: 160 Kasuganocho, Nara, 630-8212

Second Rotation: Every day, June 11th to August 4th

10am – 5pm (last entrance 4:30pm)

Admission: General: 500 yen; University and High School students: 300 yen, Junior High and Elementary School students: 200 yen. For groups of over 20, General Admission 400 yen

01

FIND YOUR FAVORITE

TRIP ON OUR WEBSITE.

SEND US AN INQUIRY.

02

PERSONALIZE THE TRIP

TO YOUR INTERESTS

WITH OUR CONSULTANT.

03

20% DEPOSIT TO CONFIRM.

BALANCE PRIOR TO ARRIVAL.

PAYMENT BY CC OR TT.

04

WE WILL

MEET YOU

AT THE AIRPORT.

05

DISCOVER THE

TREASURES!